Brian Of Nazareth

Well-known member

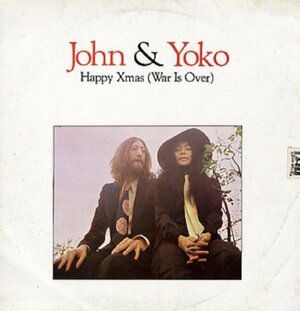

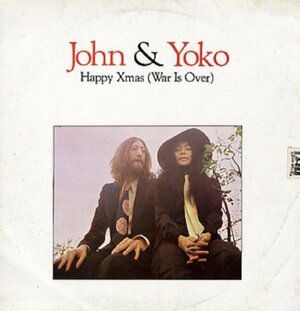

Happy Xmas (War Is Over) has always fascinated me because it isn’t really a Christmas song in the usual sense. It started back in 1969, when John and Yoko put up huge billboards around the world with the message “War Is Over! If You Want It – Happy Christmas from John & Yoko.” Two years later, Lennon basically turned that slogan into a song. He’d realised that serious ideas sometimes land better when they’re wrapped in something warm and familiar, and the idea of releasing a Christmas record gave him a way to slip a peace message into the mainstream without it feeling like a lecture.

The tune itself feels instantly familiar because Lennon based it loosely on the old folk ballad “Stewball.” It’s got that simple, memorable feel that folk songs naturally have, and the gentle 3/4 rhythm makes it sound like a traditional carol. The chords move in a way that gives it a mix of hopefulness and sadness, which quietly sits under the lyrics.

The words are incredibly straightforward but carry much more weight than people often realise. That opening line – “So this is Christmas, and what have you done?” – is Lennon challenging the listener rather than setting any kind of cheerful scene. All the little contrasts in the lyrics, like “the weak and the strong,” “the rich and the poor,” remind you that Christmas doesn’t erase inequality or conflict. Even the supposedly warm wish for a “happy New Year” ends with the far more powerful hope that the year might be “without any fear.” It’s a Christmas song that asks you to think, rather than just feel festive.

When it was recorded at Record Plant East in New York in late October 1971, Lennon and Ono brought in a brilliant group of musicians who shaped the sound of the record. Four different acoustic guitarists — Hugh McCracken, Chris Osbourne, Teddy Irwin and Stuart Scharf — created that big, layered guitar texture underneath everything. Nicky Hopkins added the piano, chimes and glockenspiel, which give it that twinkly, wintery feel. Jim Keltner played the drums and sleigh bells, and May Pang added extra vocals. Roy Cicala engineered the whole thing, and Spector co-produced it with his usual love of echo and layers. Lennon handled the lead vocal and guitar, and Yoko added her parts around his.

The moment the Harlem Community Choir arrived, the song took on its final shape. Around thirty children came in on the 30th of October to record the chants and backing lines, and their voices give the track its warmth and sense of togetherness. Before anything else was recorded, Lennon and Ono both whispered Christmas messages to their children — “Happy Christmas, Kyoko” and “Happy Christmas, Julian.” Those little moments often get misheard online, but they’re actually deeply personal touches hidden right at the start of a very public song.

Phil Spector’s production glued everything together into something unmistakably “Christmas.” The layers of acoustic guitars, the echo, the bright chimes and bells — and finally that chant of “War is over if you want it” that fades away like a crowd slowly disappearing into the distance — all create a record that sounds festive but carries a message far bigger than the season.

It was released in the US in December 1971, though publishing issues delayed it in the UK until late 1972. It didn’t explode straight away, but over time it found its place, and after Lennon’s passing in 1980 it climbed to number two in the UK charts. Since then it’s become one of those Christmas songs that returns every single year without fail. It’s now in the top three played Christmas songs of all time. John never got to see its true success and appreciate that’s it’s now a true classic.

What I like most about it is that it still works on two levels: it’s warm and nostalgic, but it also gives you that little nudge to think about the world and your part in it. It’s a peace song hiding inside a Christmas record, and that’s probably why it still feels just as relevant now as it did when Lennon wrote it.

The tune itself feels instantly familiar because Lennon based it loosely on the old folk ballad “Stewball.” It’s got that simple, memorable feel that folk songs naturally have, and the gentle 3/4 rhythm makes it sound like a traditional carol. The chords move in a way that gives it a mix of hopefulness and sadness, which quietly sits under the lyrics.

The words are incredibly straightforward but carry much more weight than people often realise. That opening line – “So this is Christmas, and what have you done?” – is Lennon challenging the listener rather than setting any kind of cheerful scene. All the little contrasts in the lyrics, like “the weak and the strong,” “the rich and the poor,” remind you that Christmas doesn’t erase inequality or conflict. Even the supposedly warm wish for a “happy New Year” ends with the far more powerful hope that the year might be “without any fear.” It’s a Christmas song that asks you to think, rather than just feel festive.

When it was recorded at Record Plant East in New York in late October 1971, Lennon and Ono brought in a brilliant group of musicians who shaped the sound of the record. Four different acoustic guitarists — Hugh McCracken, Chris Osbourne, Teddy Irwin and Stuart Scharf — created that big, layered guitar texture underneath everything. Nicky Hopkins added the piano, chimes and glockenspiel, which give it that twinkly, wintery feel. Jim Keltner played the drums and sleigh bells, and May Pang added extra vocals. Roy Cicala engineered the whole thing, and Spector co-produced it with his usual love of echo and layers. Lennon handled the lead vocal and guitar, and Yoko added her parts around his.

The moment the Harlem Community Choir arrived, the song took on its final shape. Around thirty children came in on the 30th of October to record the chants and backing lines, and their voices give the track its warmth and sense of togetherness. Before anything else was recorded, Lennon and Ono both whispered Christmas messages to their children — “Happy Christmas, Kyoko” and “Happy Christmas, Julian.” Those little moments often get misheard online, but they’re actually deeply personal touches hidden right at the start of a very public song.

Phil Spector’s production glued everything together into something unmistakably “Christmas.” The layers of acoustic guitars, the echo, the bright chimes and bells — and finally that chant of “War is over if you want it” that fades away like a crowd slowly disappearing into the distance — all create a record that sounds festive but carries a message far bigger than the season.

It was released in the US in December 1971, though publishing issues delayed it in the UK until late 1972. It didn’t explode straight away, but over time it found its place, and after Lennon’s passing in 1980 it climbed to number two in the UK charts. Since then it’s become one of those Christmas songs that returns every single year without fail. It’s now in the top three played Christmas songs of all time. John never got to see its true success and appreciate that’s it’s now a true classic.

What I like most about it is that it still works on two levels: it’s warm and nostalgic, but it also gives you that little nudge to think about the world and your part in it. It’s a peace song hiding inside a Christmas record, and that’s probably why it still feels just as relevant now as it did when Lennon wrote it.